The Risk of “Riskless” Investments

Since 2009, investors have had very little opportunity to earn a yield on their cash. However, interest rates have risen dramatically in the last two years as the Federal Reserve has aggressively tightened monetary policy, allowing investors to earn upward of 5% with money market funds, high-yield savings accounts, Treasury bills (T-bills), etc. In contrast, cash equivalents earned essentially nothing as recently as early 2022. The surge in short-term interest rates has many investors considering whether to allocate more to cash equivalents. Earning 5%, essentially risk-free, seems very attractive, especially after an era of extremely low interest rates. But is there risk to allocating a greater portion of your investments to cash?

Having highly-liquid, low-volatility savings available for near-term expenses and unforeseen circumstances is always prudent, but holding extra savings can have negative consequences. First, cash equivalents tend to underperform riskier investments (e.g., stocks) over the long term. This reality is broadly understood; however, even shifting from lower-risk, lower-return investments (e.g., bonds) to cash introduces risk. Holding cash instead of bonds may seem innocuous, especially in the current yield environment, when cash earns a higher rate than bonds. Intuitively, one might assume that the higher-yielding, less-risky investment is preferable, but the concealed danger of holding excess cash lies in reinvestment risk.

Reinvestment risk is the risk that you’ll have to reinvest a maturing investment at a yield lower than the current rate. For example, if you have a five-year investment horizon but buy 30-day T-bills, you will have to reinvest the proceeds each month at whatever the prevailing rate is at that time. That yield could be substantially lower than the current yield. In contrast, you could buy a five-year bond and lock in a fixed yield for your entire investment horizon. In this scenario, 30-day T-bills (which are less risky in an absolute sense) are riskier than a five-year bond due to the mismatched timeframes.

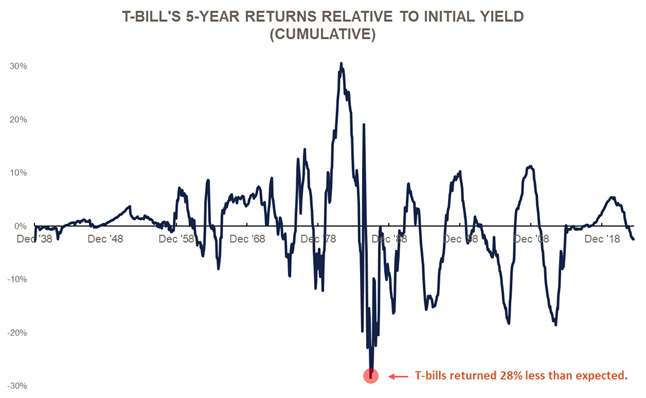

To help quantify the reinvestment risk of cash equivalents, we can look at how 30-day T-bills’ five-year returns have historically diverged from their starting yields (see chart below). On average, T-bills’ five-year cumulative returns have been +/- 5% from what would have been expected based on their initial yield. In the worst case, T-bills returned 28% less than expected!

Source: Ibbotson SBBI

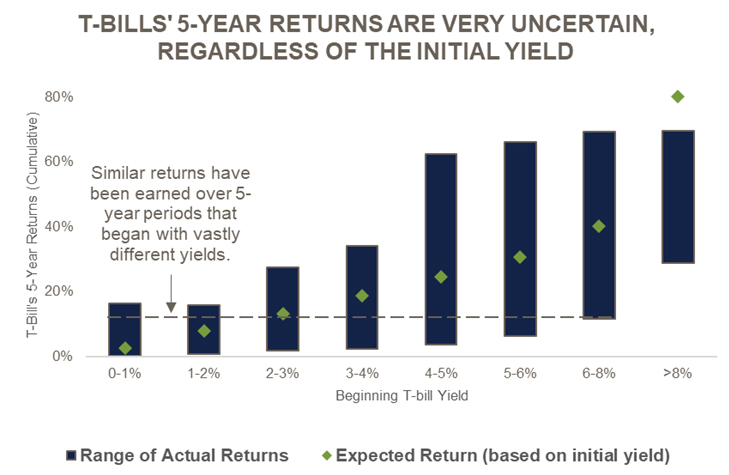

While it’s true that the higher the beginning yield, the more T-bills have returned on average, the range of returns has been exceptionally wide. In fact, there have been five-year periods when investing at an initial yield greater than 6% resulted in a lower return than some periods that began with yields below 1%. The chart below displays the range of T-bill returns earned over five-year periods, sorted by the beginning T-bill yield.

Source: Ibbotson SBBI

The current T-bill rate falls in the 5‒6% range. This yield may seem attractive, as compounding returns at 5‒6% for five years would generate cumulative returns of roughly 30%. However, due to reinvestment risk, there’s no guarantee that returns will compound at that rate. Historically, initial yields of 5‒6% have resulted in cumulative returns over five years of between 6‒66%, a considerable deviation from a dependable 30%.

The irony about seasons like today, when cash has a higher yield than bonds, is that these times have historically been some of the worst periods for cash relative to bonds. This underperformance has followed inverted yield curves because these periods were usually characterized by tight monetary policy, which caused a recession when interest rates typically decline, reducing the return of cash as it’s reinvested at lower yields but boosting the return of bonds since they appreciate due to their high fixed rates. These periods have also often coincided with negative equity returns, so swapping bonds for cash equivalents could reduce overall portfolio resilience if economic stress develops.

Ultimately, if you are thinking about allocating a greater portion of your investments to cash, you should carefully consider your financial goals, risk tolerance, and investment time horizon. While having liquid savings for short-term expenses and unforeseen circumstances is essential, overcommitting to cash equivalents introduces additional risk.

If you would like to learn more about Ronald Blue Trust’s time-based investment approach or cash management services, please contact your advisor.

As with any investment strategy, there is potential for profit as well as the possibility of loss. Ronald Blue Trust does not guarantee any minimum level of investment performance or the success of any investment strategy. All investments involve risk and investment recommendations will not always be profitable. Diversification does not guarantee investment returns and does not eliminate loss. Past performance does not guarantee future results.